Two comments on your BM2022 example:

Consumption taxes. I think you forgot to include consumption taxes when defining total tax revenues in line 116 of your main scirpt:

FnsToEvaluate.TaxRevenue=@(h,aprime,a,z,r,tau,xi,iota,delta,alpha,tau_a,xi_a) BM2022_IncomeTaxRevenue(h,aprime,a,z,r,tau,xi,iota,delta,alpha) + BM2022_WealthTaxRevenue(h,aprime,a,z,tau_a,xi_a);

In fact, the government collects taxes on personal income, wealth and consumption (the consumption tax rate is \tau_s).

Improve general equilibrium algorithm. If I choose fminalgo=5 (shooting), I set

GEPriceParamNames_pre = {'r','iota','B','G'};

heteroagentoptions.intermediateEqns.K=@(A,B) A-B; % physical capital K: A is asset supply, K and B are asset demand

heteroagentoptions.intermediateEqns.Y=@(K,L,alpha) (K^(alpha))*(L^(1-alpha)); % output Y

% --- Interest rate equals marginal product of capital (net of depreciation)

GeneralEqmEqns_pre.capitalmarket = @(r,K,L,alpha,delta) r-(alpha*(K/L)^(alpha-1)-delta);

% --- Calibration target iota/Y

GeneralEqmEqns_pre.iotacalib = @(iota,iota_target,Y) iota_target - iota/Y; % get iota to GDP-per-capita ratio correct

% --- Calibration target B/Y

GeneralEqmEqns_pre.govdebtcalib = @(Bbar,B,Y) Bbar - B/Y; % Gov Debt-to-GDP ratio of Bbar

% --- Balance the goverment budget

GeneralEqmEqns_pre.govbudget = @(r,B,G,TaxRevenue) r*B+G-TaxRevenue;

% Option for shooting algo

heteroagentoptions.fminalgo5.howtoupdate={... % a row is: GEcondn, param to adjust, add (if 1), factor

'capitalmarket','r',0,0.05;... % CapitalMarket GE condition will be positive if r is too big, so subtract

'iotacalib','iota',1,0.05;... % govbudget GE condition positive if iota is too small, so add

'govdebtcalib','B',1,0.01;... % govdebtcalib condition positive if B is too small, so add

'govbudget','G',0,0.01;... % govbudget condition positive is G is too big, so subtract

};

Does this make sense to you? Unfortunately, it does not converge: in particular, the condition govbudget goes further and further away from zero after two iterations. I am wondering if I should set 1 instead of 0 for G.

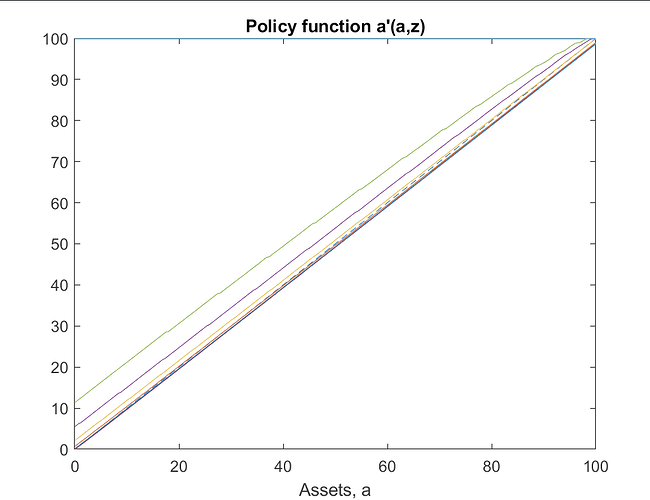

Upper bound for assets

Given the super-star shock, are you sure maxa = 100 is sufficient? If I plot the policy function a'(a,z) for the highest z, is hits the upper bound (see graph below). There are only 0.02% of agents in the super-star state, so maybe it does not transpire well if you only look at the stationary distribution.